Hypercuriosity: What If I Wasn’t Broken After All?

Hypercuriosity: What If I Wasn’t Broken After All?

I stumbled across an article recently that stopped me in my tracks: “Rethinking ADHD as Hypercuriosity” from Positive News.

Reading it felt like someone had reached back through five decades and said, “Hey, that wiggling, doodling, note-passing kid? She wasn’t deficient. She was wired for exploration.”

The article explores emerging research that reframes ADHD not as an attention deficit but as a different way of allocating attention - one oriented toward novelty, exploration, and making unexpected connections. Instead of pathologizing restless, curious minds, researchers are asking: what if these brains are actually designed for innovation and complex problem-solving?

This hit me hard because I was absolutely that kid.

Hyper = curious?

This hit me hard because I was absolutely that kid.

Elementary school was rough. I rejected worksheets and book reports with the kind of stubborn conviction that makes teachers sigh deeply. I wiggled. I doodled. I chatted. I passed notes. The feedback was consistent and clear: I was a problem. Too much energy. Too easily distracted. Not following directions.

Here’s the thing though - my teachers also knew I was smart. I learned easily. I tested well. The contradiction must have been maddening for them. What do you do with a bright kid who simply won’t comply with the structures designed to educate her?

Project Adventure in seventh grade was like oxygen. Finally, a program built around experiential learning, physical challenge, group dynamics, and problem-solving. I thrived. High school was better too, once I had more choice in what I studied and how I spent my time. But those elementary years? They left their mark.

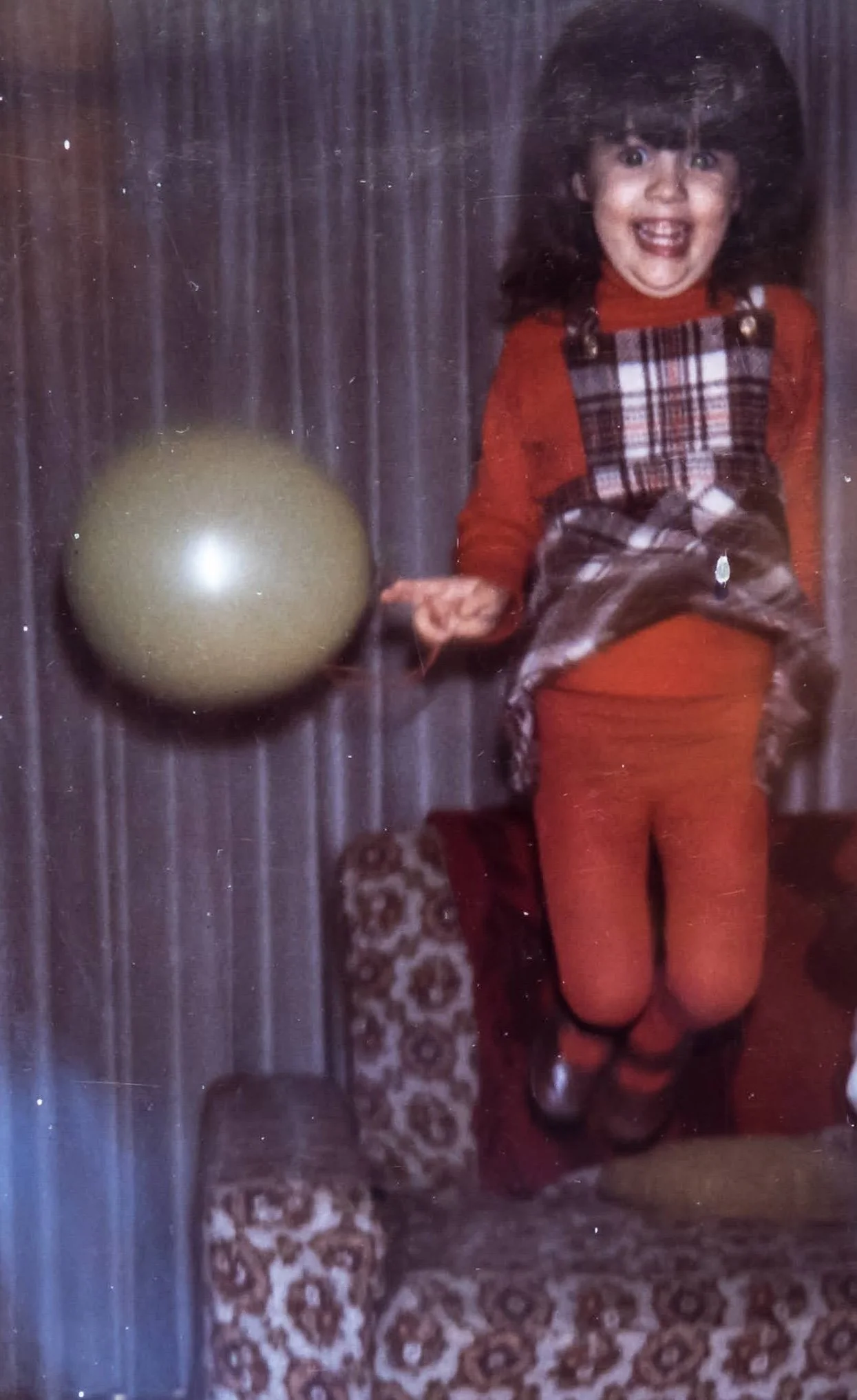

Recently, I asked my mother if she thought I would have been diagnosed with ADHD if more had been known in the 1970s. She looked at me with love and warmth, smiled, and said simply: “Oh yes.”

That response captures everything about why I made it through those years with my sense of self intact. My parents listened patiently to my teachers, I’m sure. They probably nodded sympathetically through countless parent-teacher conferences about my “challenges.” But they never brought that energy home to me. They never made me feel ashamed. Instead, they seemed proud of my strong spirit, even when it made things harder.

That unconditional support was everything. While the school system was telling me I was too much, my parents were quietly communicating: you’re exactly right just as you are.

The article describes how hypercurious individuals often feel like they’re “too much” in traditional settings but become invaluable when complexity increases and innovation is needed. Reading that, I thought about my career path - from launching entire product lines at Gap (intrapreneurial roles that required seeing possibilities others missed or felt too afraid the try) to building a coaching and facilitation practice centered on helping people and organizations navigate complexity and change.

My work now requires exactly the kind of brain that drove my elementary teachers to distraction. Holding multiple perspectives simultaneously. Making lateral connections. Pivoting quickly when new information emerges. Synthesizing disparate ideas into something new. Thriving in environments with autonomy and variety rather than rigid structure.

What if that restless, curious, sometimes disruptive kid wasn’t broken? What if she was just designed for a different kind of work - the kind our increasingly complex world desperately needs?

I think about the clients I work with now, particularly the ones who describe themselves as “too intense” or “always questioning everything” or “easily bored by routine.” The ones who were probably challenging students themselves. I see their hypercuriosity not as something to manage but as their superpower, particularly when they can find or create environments that channel it well.

My energy pushes against constraint and champions creativity and authenticity. That combination made elementary school feel like a cage. But it’s also what makes me good at what I do - creating space for others to access their own expansive thinking, to question outdated playbooks, to move through discomfort toward innovation.

So here’s what I want to say to anyone who was told they were too much, too distracted, too questioning: What if you weren’t the problem? What if you just needed different channels for that brilliant, pattern-seeking, novelty-loving brain?

And if you’re a parent of a hypercurious kid who’s getting feedback that sounds familiar, remember this: your job isn’t to make them fit better into systems that weren’t designed for how they think. Your job is to help them know, bone-deep, that their strong spirit is something to be proud of.

My parents did that for me. It made all the difference.

My Mom and Dad with us on our wedding day in 2004.